Alternative Fuels Part 4: Decentralised decarbonisation with bioLNG

Liquified natural gas (LNG) has been described both as the best available fuel for decarbonisation today and as a dead end. Its molecular cousin liquified biomethane (LBM), or bioLNG, could soon provide a less disputable greener alternative.

Roel Engels was brought into the Titan fold to head up its Amsterdam plant project. Titan is in the process of building what is set to become the world’s biggest biomethane liquefaction plant. It will supply ships handling cargo in the Port of Amsterdam and the wider ARA hub.

The plant will have capacity to produce 200,000 mt/year of LBM straight away, without any phasing. Demand for LBM is expected to be driven by various upcoming environmental regulations. Shipping’s inclusion in the EU’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) will be one, but there is also FuelEU Maritime, the current Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) and the Energy Tax Directive, Engels points out.

“Those are examples of regulations pushing LBM demand in shipping. And there is also a clear push from the end consumers demanding green containers. So it’s both regulatory and voluntary demand” he says.

Nicolas Ganas has worked on various LNG bunker projects for Titan as a business development manager and senior trader. LNG bunker operations are not as straightforward as delivering fuel oil and gasoil to ships. Every LNG delivery to a ship requires careful planning to maintain cryogenic temperatures and specific pressures. Valves need to fit properly and rigorous safety protocols need to be followed to the point.

Same molecule

LBM can function as a drop-in fuel in LNG, much like biofuels have been blended with VLSFO or MGO in an increasing number of recent trials by shipowners. This means that vessels capable of running on LNG will not have to make any modifications to run on pure LBM or LBM-LNG blends.

“Physically it’s the same molecule, it’s just CH4, methane,” Engels says, “…and I think that’s a good thing about LBM. You can obviously use it in pure form, but you can also use it as a drop-in fuel to make the transition more gradual.”

It will be up to the customer whether to blend it with LNG at a certain percentage as a drop-in fuel per bunkering or whether it will be averaged across the fleet. Part of the fleet can run exclusively on LNG, and part on LBM for example.

Well-to-wake

If LBM and LNG are virtually made up of the same molecule, their emissions profiles should conceivably be the same. So why is LBM considered a more environmentally friendly alternative to LNG?

LBM and LNG are more or less the same fuels when they are injected into an internal combustion engine, and they will have similar tank-to-wake emissions on a ship. But they are not produced in the same way and therefore their environmental credentials vary.

“If you just look at the ship stack, the molecule is the same. It is how it was made that really matters,” Ganas says.

“The origin of CO2 is different from the fossil LNG,” Engels explains. LNG “is extracted from underground where it has been stored for millions of years, whereas the CO2 from the LBM or e-methane is in the short-cycle. All the time biomass is growing and dying. It’s a natural cycle of carbon being stored, captured and released again.”

All things considered, it’s important to have a well-to-wake assessment, Ganas stresses.

“What I think is positive for us as a supplier is that we see more and more of a big push from shipowners for a well-to-wake approach,” he says. “We want that because when you burn that LBM or e-LNG, you need to have a well-to-wake approach to show the benefits. To show that you have 80% reductions in greenhouse gases, or even more than 100%.”

Engels says that a typically-sourced bioLNG blend of 20% LBM and 80% LNG can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 18% on a tank-to-wake basis compared to LNG. This is in addition to the reductions already achieved with burning LNG compared to conventional oil-based fuels. With 100% LBM the reduction can reach up to 93% in the combustion cycle. That reduction can be even greater on a well-to-wake basis, depending on the LBM feedstock and how it is produced and distributed.

“It really comes from the bigger argument, that common sense that whether you’re in biomethane, biofuels: you have to be accountable for how you source that feedstock, how you process it, to do it in a more sustainable way,” Ganas says.

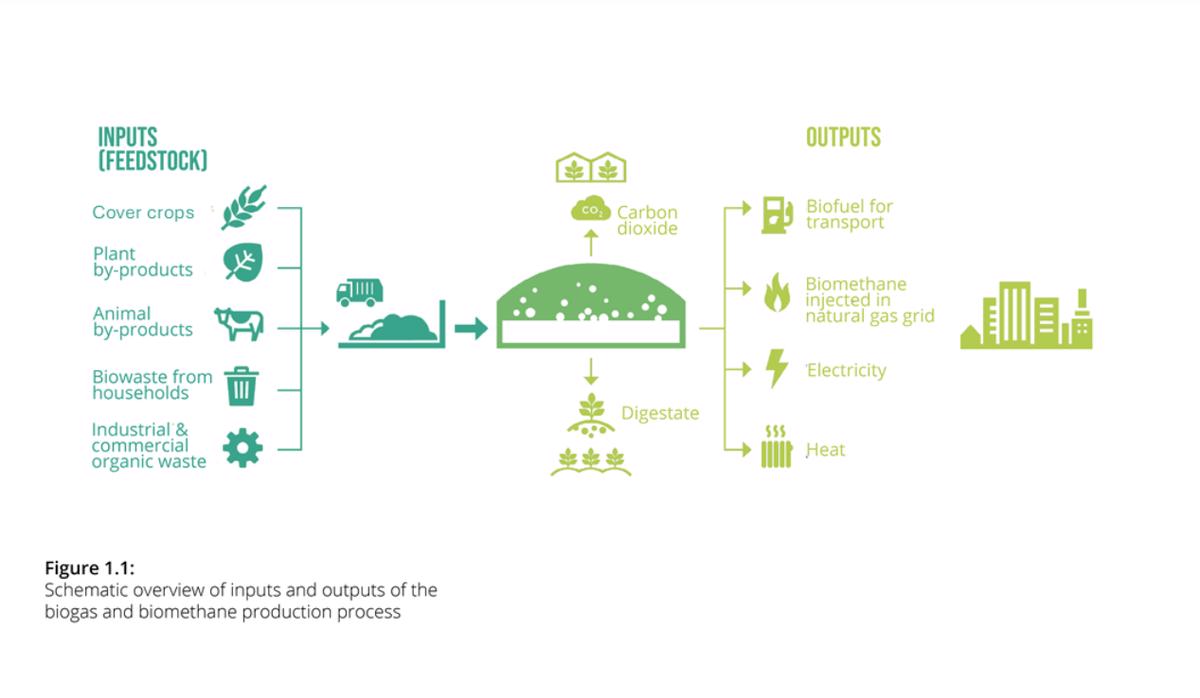

CHART: Production and uses of biogas and biomethane. European Biogas Association

CHART: Production and uses of biogas and biomethane. European Biogas Association

LBM from biogas

So how is biomethane feedstock sourced, processed and liquified?

Unlike LNG’s fossil origin, LBM comes from biogas, which, in turn, comes from anaerobic digestion of organic waste streams. This organic matter has previously worked as a carbon sink in that it sucks CO2 out of the atmosphere - like plants that grow in part through absorbing CO2.

The organic matter for biogas production can also come from sources like household waste, animal manure and sewage sludge. These are waste streams that emit biogas composed of methane and CO2 during anaerobic digestion.

The biogas has to pass through one crucial step. It needs to be upgraded to so-called green gas by removing CO2 prior to the gas going through a liquefaction plant to allow for economical transport to the end user.

PHOTO: Biogas is upgraded to green gas by removing CO2 in a purification plant. BioValue

PHOTO: Biogas is upgraded to green gas by removing CO2 in a purification plant. BioValue

“You have the big silo where anaerobic digestion takes place, and then usually a membrane system to bring it up to spec to feed it into the gas grid,” Engels explains.

The separated CO2 part can then be combined with hydrogen to produce e-methane at a later stage.

“This will not be from day one because there are some challenges,” Engels says. “The first is availability of sufficient and affordable green hydrogen, and the connection to the Hydrogen Backbone. But it would be a nice route to valorise the biogenic CO2, dependent on the hydrogen part.”

Local and decentralised biogas

Titan’s upcoming Amsterdam liquefaction plant will be fed with biogas from two different sources, Engels explains. The first is a local biogas plant in Amsterdam that will be built by Titan’s partner BioValue. Raw biogas from BioValue’s plant will flow into Titan’s liquefaction plant.

Titan’s other source is from a grid that is fed with purified biogas, or green gas, from producers across Europe in a mass-balance system. In a mass-balance system, fossil and renewable gas can be mixed, but their quantities are recorded and accounted for throughout the system.

Engels says that biogas is most efficiently produced when biogas plants are decentralised. That way, organic feedstocks do not have to be transported over long distances. Smaller biogas plants can be spread across geographical distances to benefit from existing gas grid infrastructure.

The liquefaction part of LBM production, on the other hand, makes more sense to do centrally because of scale advantages and to avoid micro scale production and transportation over land, he says. Titan’s liquefaction plant will be situated right next to its bunker infrastructure in the Port of Amsterdam, from where LBM will be supplied to ships and trucks after 2025.

To ramp up production of LBM to improve economies of scale, Engels says, “you need to stimulate both sides. The production of biogas, and we also need to stimulate the infrastructure development around the liquefaction part.”

Delivery barge crunch

Titan was at first more exclusively focused on LNG bunker supply, and it has also made several recent investments in bolstering its onshore and barge LNG delivery infrastructure. Ganas points to DNV numbers when he argues that the supply side of LNG bunkering is likely to fall short of demand as more LNG- and LBM-fuelled vessels enter the global fleet.

“On the barge side it has not been keeping up,” he says.

According to DNV data, 109 ships capable of running on LNG entered the global fleet last year, bringing the total to 355 in operation. These ships can be bunkered by a fleet of 42 LNG bunker delivery vessels. But while the number of LNG-fuelled ships is projected to more than double to 870 by 2028, there are only 19, or 45%, additional LNG bunker delivery vessels on order.

An inflection point, with demand rising above LNG barge delivery capacity, could materialise in the middle of this decade. But right now there is enough barge capacity, after a period of skyward gas prices and gas-to-oil switching among shipowners.

Rotterdam’s LNG bunker sales had been rising consistently quarter-on-quarter until 2022. In the third quarter of 2022, sales were down by a massive 47% compared to a year earlier. This was largely a result of high gas prices incentivising shipowners with dual-fuel engines to burn VLSFO or MGO instead of LNG.

“The numbers have come down of course since the invasion of Ukraine and the disruption of the market,” Ganas says. “But when things will normalise again there could be a situation where not enough barges were built in the meantime, and it’s costly so you have to think hard before you invest your hard-earned money to build a barge.”

EU regulatory support needed

Regulatory incentives can spur more investments into LBM production and stimulate uptake from ships. The EU made a massive breakthrough at the end of last year, agreeing to include shipping into its cap and trade Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) for the first time. Starting from 2024, CO2 emissions allowances will be phased in to eventually cover 100% of CO2 emissions from ships within three years. The ETS will make it progressively more costly to burn carbon-intensive fuels for ships sailing to and from and between EU ports.

“The push has always been there and it’s coming from the shipowners,” Ganas says. As the EU ETS will not come into effect in 2023, he points out, the World Shipping Council and a range of other shipping organisations have said we should use this time to work a well-to-wake emissions approach into the ETS.

“Because then it’s going to meet the FuelEU Maritime, which is more like the adoption of alternative fuels. Then it’s going to be a nice way to merge both.”

By Erik Hoffmann

Please get in touch with comments or additional info to news@engine.online