EU shouldn’t lower the bar by aligning with the IMO – NABU

Aligning the EU’s regional shipping regulations with the IMO’s planned global framework will be difficult, but the EU must hold onto its climate ambition, NABU’s Lukas Leppert told ENGINE.

The IMO’s Net-Zero Framework (NZF) will be up for adoption at the Marine Environment Protection Committee’s extraordinary session (MEPC ES.2) next week. If the NFZ gets adopted, ships calling at EU ports would have to comply with both this global regulation and the EU’s FuelEU Maritime and EU ETS regulations from 2028.

These regulations are have different rules and limits.

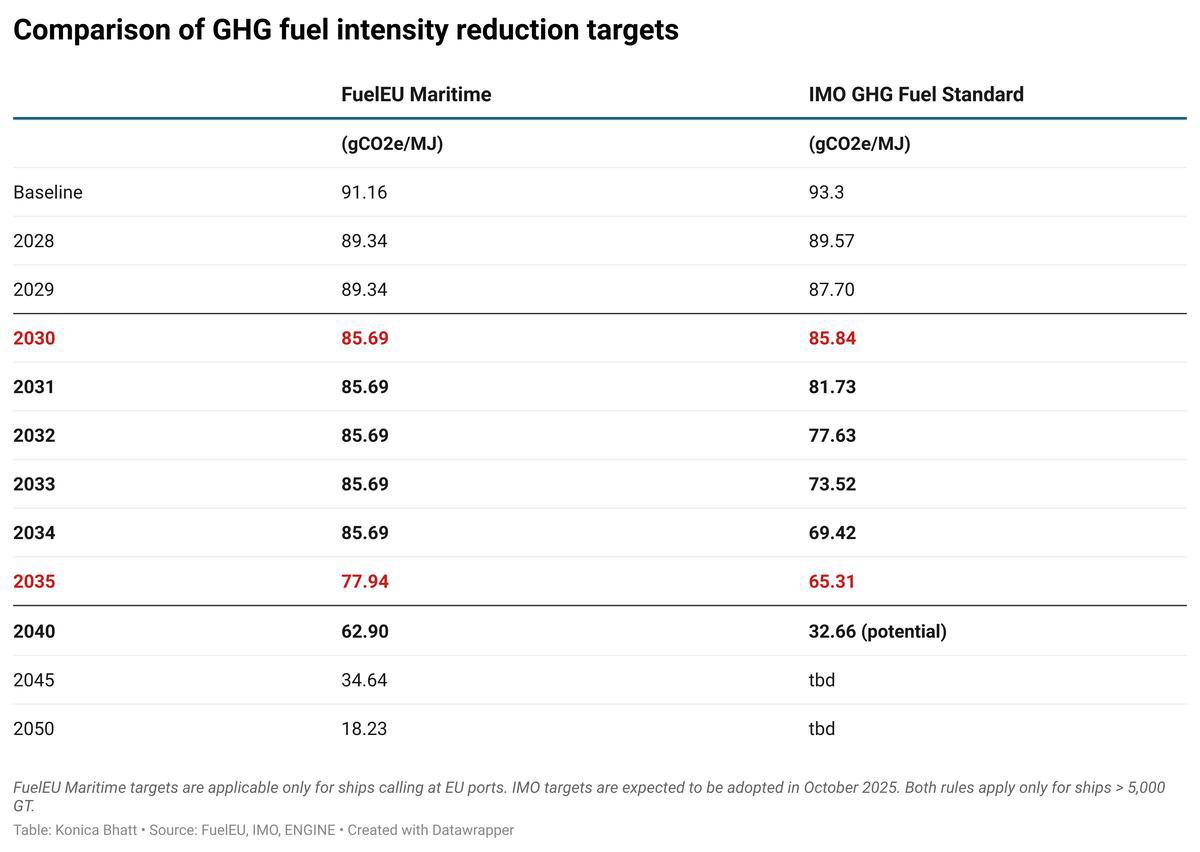

For example, the IMO’s approved framework will cap the greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity of energy used onboard ships to 65.31 grams of carbon dioxide-equivalent per megajoule (gCO2e/MJ) by 2035, using 2008 levels as its baseline.

FuelEU Maritime sets a softer target of 77.94 gCO2e/MJ by the same year and benchmarks against 2020 levels.

The IMO draft framework imposes a fee for non-compliance, but stops short of a carbon price, while the EU’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) places a direct cost on emissions.

This inconsistency could create a double compliance burden for vessels operating between EU ports.

German non-profit Naturschutzbund Deutschland (NABU) argues that both the EU’s regional and the IMO’s global shipping regulations must coexist to genuinely decarbonise the sector. But aligning the two systems will be “challenging,” Lukas Leppert, shipping policy officer at NABU, told ENGINE.

In March, the IMO's Secretary-General Arsenio Dominguez urged the EU to align with the IMO’s planned global framework. Leppert warned that “it would be a major setback for the EU to drop its environmental and climate regulations merely to align with global rules of lower stringency.”

Lukas spoke to ENGINE in an exclusive interview with Konica Bhatt.

NABU argues that both EU and IMO regulations are needed to decarbonise shipping, yet their designs differ in scope and ambition. Will these variations drive real-world emission reductions, or risk creating a gap that ultimately weakens overall progress?

The two systems of regulations have differences but will support each other in reaching maritime decarbonisation targets.

The existing EU regulation and the upcoming IMO regulations, which are to be adopted next week, both aim to reduce the climate impact of shipping. They are similar, since both require a reduction of the GHG intensity of shipping fuels and put a price on GHG emissions. However, the IMO NZF lacks essential technical elements and climate safeguards that are included in the EU framework. For example, it does not allow first-generation biofuels, known for their high (and unaccounted) ILUC [indirect land-use change] emissions, to count towards GHG reduction.

FuelEU also contains, even if limited, initiatives for truly sustainable fuels made from green hydrogen, and it includes provisions for mandating shore-side electricity in ports. These supporting regional regulations are necessary to fill gaps not addressed by the IMO. Their role is not to cause fragmentation but to help reach the global maritime decarbonisation targets, which would not be possible with the NZF alone.

NABU points out that the IMO’s pricing structure could boost demand for biogenic fuels, while the EU favours renewable e-fuels uptake on ships. Could such a misalignment distort fuel investment flows and delay the global e-fuel uptake needed to meet tightening targets?

The EU’s policies have correctly identified that shipping will require renewable e-fuels based on green hydrogen. IMO member states, at least collectively, seem not to agree on that long-term perspective.

The challenge is the high prices of these premium fuels and the fact that the IMO's penalties aren't sufficiently stringent to incentivise their uptake, failing to send much-needed early investment signals.

The EU faces similar problems of high initial costs but has a safety mechanism in place by setting a minimum quota for these green e-fuels. Therefore, the biggest risk I see is that necessary investment in hydrogen production will go towards unsustainable short-term solutions like biogenic fuels and LNG. These are sunk investments and will cause further GHG emissions, either due to methane slip, deforestation, or land-use change. Delaying the solution today will only lead to stranded assets, higher pressure to act, and rising investment needs tomorrow, while improvements in the short term remain doubtful.

Do you see a risk that overlapping penalties could inflate compliance costs without necessarily improving climate outcomes?

First of all, I would like to highlight that these penalties reflect the principle of responsibility, not the principle of punishment.

To answer the question, a possible future overlap will only affect 10–15% of greenhouse gas emissions. While it was under discussion, the proposed IMO NZF does not include a flat levy on all GHGs but two levels of penalties for ships that fail to bunker sufficiently clean fuels.

Still, double-pricing the same tonne of GHG should be avoided if possible.

It would be preferable for the IMO to have a single global policy framework as a baseline, with regional measures providing targeted incentives and safeguards. Due to differing levels of ambition, as well as diverging national priorities, such a global agreement could not be reached. In this case, the cost of overlapping penalties and GHG prices needs to be weighed against the additional administrative burden of harmonising them.

Since the IMO mechanism will cover only about 10–15% of global shipping’s GHG emissions, the EU should avoid reducing its scope beyond what is needed to compensate for liabilities under the IMO while also considering the administrative burden.

How do you think dual regulatory regimes will impact global trade?

I don't expect a significant impact on global trade. The EU pricing regulations have been in place since 2024. In its first assessment of the carbon market for shipping, the European Commission found no evidence of trade rerouting through Union ports.

While it remains a theoretical possibility, I want to highlight that shipping already operates under a multitude of geopolitical tensions and price fluctuations due to changes in routes in response to the Red Sea crisis, fuel markets, and regulations such as tariffs. All of these impose higher costs than environmental regulations and have been weathered by the industry.

The pricing mechanism on greenhouse gases is comparatively low, while alternative fuels have time to scale, mature, and benefit from long-term investment if proper incentives are provided.

What is the one design feature from the EU system that the IMO must adopt to make its Net-Zero Framework truly effective?

The EU’s framework includes multiple technical regulations that improve its effectiveness compared to the IMO NZF.

If I had to limit myself to copying one, it would be the exclusion of biogenic fuels from feed and food crops like soy and palm oil, which have a high ILUC impact. Due to their high indirect land-use emissions, these fuels are often more polluting than the fossils they are meant to replace and could cause a rise in GHG emissions in the foreseeable future instead of supporting the goals set out in the IMO GHG Strategy 2023.

Member states should do their best to reflect these impacts in the upcoming work on guidelines. However, the previously mentioned technical measures, such as additional support for e-fuels and shore-side electricity, are also worth considering.

What kind of coordination mechanism is needed to prevent double counting of emission reductions and promote alignment between regional EU regulations and global IMO regulations?

At their core, the EU and IMO policies prevent the threat of double-counting emission reductions by accounting for total GHG reductions in their respective fuel standards.

For ships or relevant companies that bunker clean fuels to achieve a sufficient reduction in GHG intensity, these emission reductions will be reflected under both schemes. Since no carbon credit is being issued, double-counting in the common understanding is impossible.

It might only be relevant in the context of the IMO reward mechanism or EU subsidies for climate-friendly technologies, though the issue of redundant subsidies may be a national prerogative and is already generally reflected in the EU's strict rules on state aid.

The alignment of EU and IMO regulations will prove challenging.

After working hard and sending important signals beyond its borders - not least the inception of other ETS schemes - it would be a major setback for the EU to drop its environmental and climate regulations merely to align with global rules of lower stringency. Instead, the EU can step up as a progressive leader, transferring its lessons, regulatory expertise and tested policies to facilitate the process on a global level.

The upcoming negotiations on guidelines at the IMO will offer an opportunity to advance this process.

By Konica Bhatt

Please get in touch with comments or additional info to news@engine.online