ICCT flags near-term barriers for Great Nicobar’s bunkering ambitions

The bunkering potential of India’s Great Nicobar Island faces feasibility and renewable capacity hurdles by 2030, according to a study by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT).

India’s Great Nicobar Island could, on paper, serve as an alternative bunkering location for methanol- or ammonia-capable vessels that currently refuel in Singapore.

But in practice, the island’s limited renewable energy capacity, high green hydrogen costs and environmental sensitivities restrict its near-term feasibility, the ICCT found in a study published in August.

The ICCT study builds on India’s maritime strategy - Maritime Amrit Kaal Vision 2047 – which identifies Great Nicobar as a potential bunkering and transshipment hub by 2030.

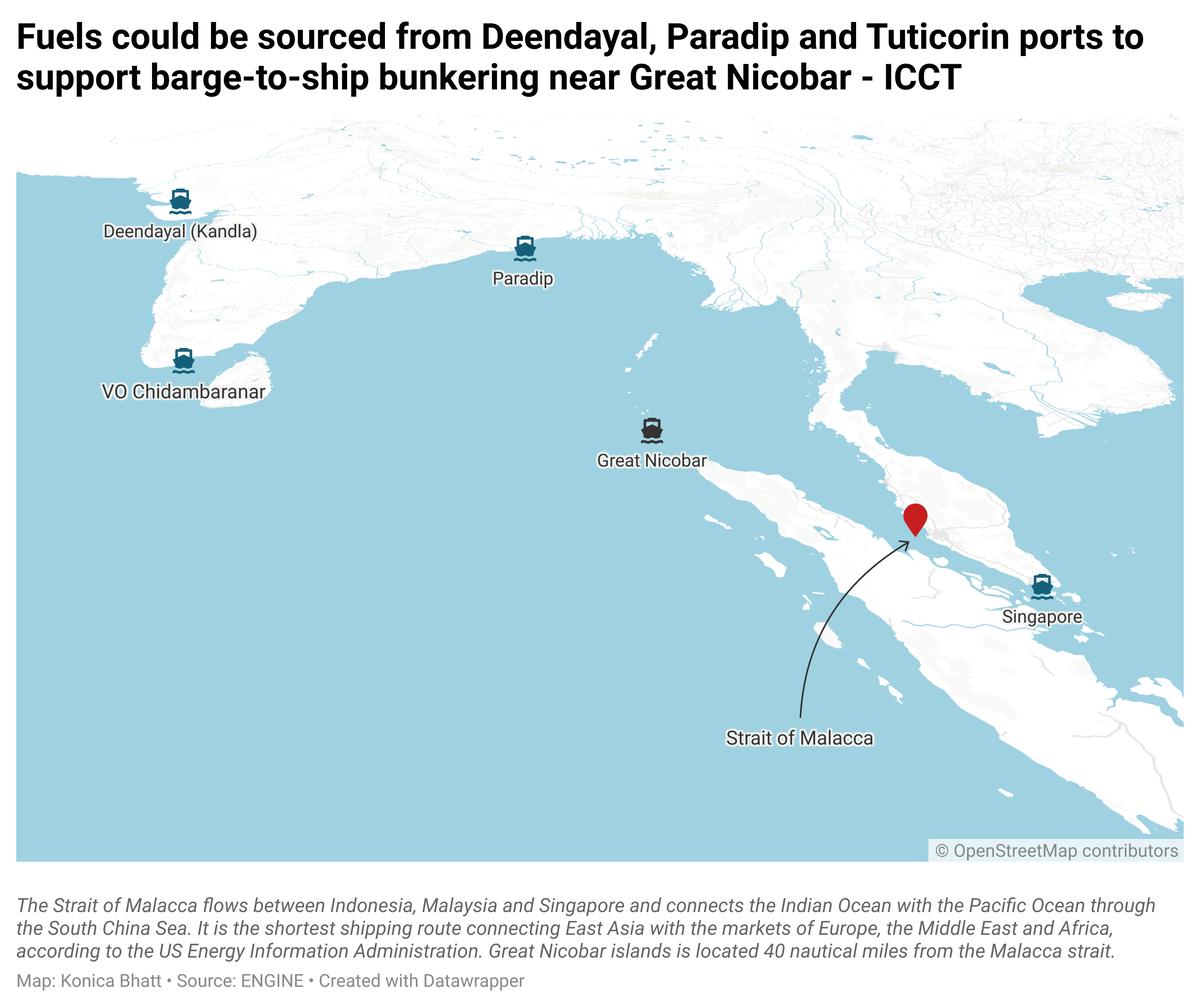

The island’s proximity to the Malacca Strait places it along one of the world’s busiest maritime routes. The Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways (MoPSW) says this location could allow ships to refuel without deviating significantly from the East-West trade route, making it geographically well-suited to serve as an alternative to Singapore.

But the ICCT’s assessment suggests the island’s potential is more theoretical in the near-term.

Around 900 container ships bunker an estimated 11.1 million mt/year of fuel in Singapore. If bunkering were to shift entirely to Great Nicobar, this capacity will translate to roughly 25 million mt/year of ammonia or 23 million mt/year of methanol “assuming a complete replacement of residual fuel demand by a single fuel type.”

Even under a modest 5% IMO 2030 alternative-fuel scenario, the island could represent an addressable market of around 1.2 million mt/year of ammonia or methanol. Producing this scale of fuel will require at least 190,000-250,000 mt/year of green hydrogen and 3.5-4.5 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy, the study estimated.

And meeting 100% of projected demand will need an even bigger 70–89 GW of renewable energy, which is almost half of India’s planned 125 GW renewable capacity for green hydrogen production by 2030.

Balancing this demand with that of other hard-to-abate sectors such as fertiliser and steel production could prove challenging. In addition, high green hydrogen production costs, logistical barriers and uncertainty around offtake can limit actual progress by 2030, ICCT highlighted.

While the island holds clear geographic advantages, the report warns that competing fuel options and unclear demand signals may require strong policy intervention to stimulate investment and lower costs.

It also flagged potential environmental and social risks, including biodiversity loss, rainforest destruction and disruption to local communities.

Although India’s maritime strategy outlines plan for hydrogen production and storage hubs across the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, renewable capacity there remains limited. Until expansion takes place, fuels would likely need to be sourced from Deendayal (Kandla), Paradip and VO Chidambaranar (Tuticorin) ports which are being developed to handle ammonia and hydrogen by 2030.

These ports can deploy bunker barges, which can serve as "floating storage" for alternative fuels and allow barge-to-ship bunkering around Great Nicobar in the near-term.

“This supply chain approach could allow refueling to occur either at berth or at sea while anchored and provide operational flexibility to vessels operating in and around Great Nicobar,” ICCT noted.

The study concluded that without clear environmental safeguards integrated into renewable energy and infrastructure planning, the island's future as a potential bunkering hub risks remaining an ambitious blueprint rather than a practical reality.

By Konica Bhatt

Please get in touch with comments or additional info to news@engine.online