Wikborg Rein on how to pool compliance with FuelEU Maritime

Pooling allows for more flexible strategies to comply with FuelEU Maritime

A pool can contain vessels controlled by different companies

Pooling may potentially be used to offset negative effects of other vessels

Pooling has a more fundamental function, to incentivise first movers

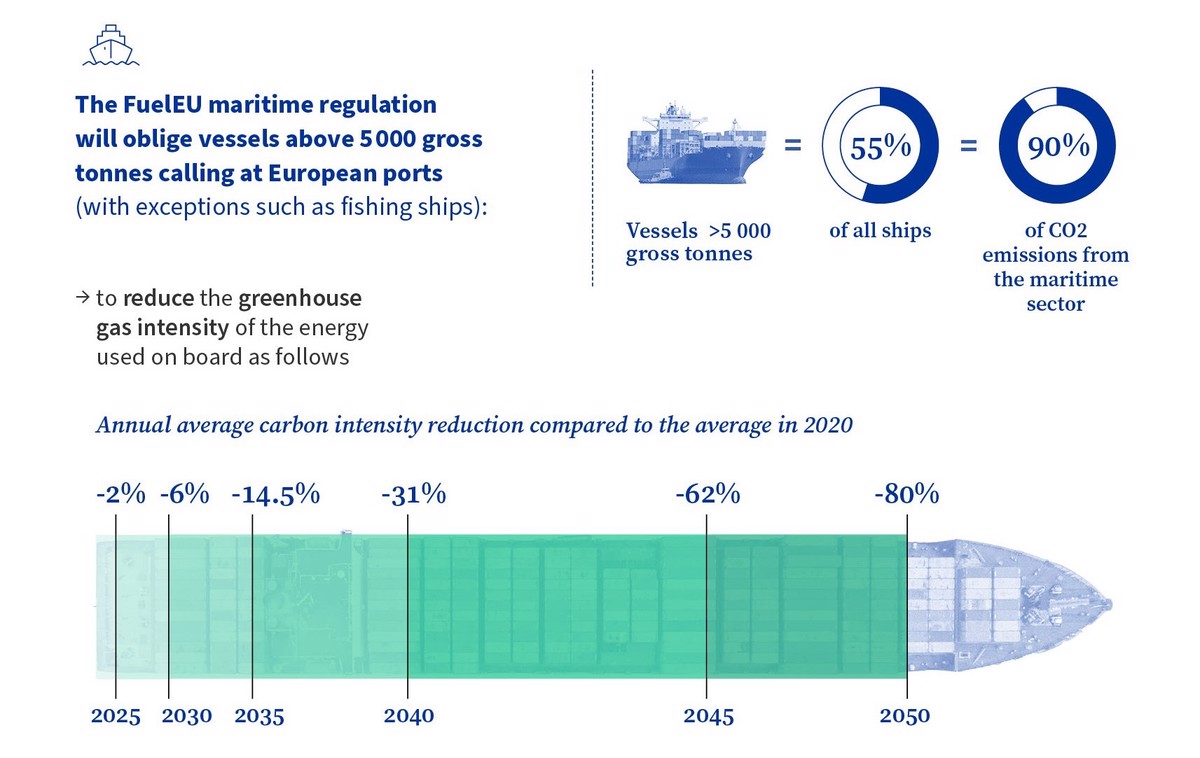

INFOGRAPHIC: Pooling can be used to comply with the EU's upcoming GHG intensity reduction targets, which will impact most vessels calling at EU ports. European Council

INFOGRAPHIC: Pooling can be used to comply with the EU's upcoming GHG intensity reduction targets, which will impact most vessels calling at EU ports. European Council

Pooling may be an important tool for shipping companies when the EU’s FuelEU Maritime regulation comes into full effect from 2025.

“The most savvy shipowners and operators will definitely look into these rules now and prepare for what is to come,” says Knut Hausken Magnussen, a senior lawyer at Norwegian law firm Wikborg Rein.

The FuelEU Maritime regulation introduces increasingly stringent limitations on the greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity of the energy used onboard vessels. It sets out targets for a 2% reduction from 2025, 6% from 2030, 14.5% from 2035, 31% from 2040, 62% from 2045 and 80% from 2050 - all compared to 2020 levels. With certain exceptions, the regulation applies to all vessels (irrespective of their flag) which serve the purpose of transporting passengers or cargo for commercial purposes and are above 5,000 gross tonnes.

Compliance with these limitations can be allocated between vessels participating in a pooling arrangement. Pooling can be done between vessels both in the same fleet and between different fleets, Magnussen says. In a pooling arrangement, the total pool compliance balance is allocated to each individual ship. In order for the pool to be valid, the total pooled compliance must be positive. In addition, each individual vessel must not have a deficit after the total pooled compliance has been allocated.

Magnussen argues that the pooling arrangement is advantageous since it creates incentives to invest in more energy-efficient vessels. Companies which have vessels with low GHG intensity in the energy used on board could potentially also seek to obtain payments or other commercial benefits as a condition for including their vessels in a specific pool.

PHOTO: Wikborg Rein senior lawyer Knut Hausken Magnussen (left), and Wikborg Rein partner Elise Johansen (right). Wikborg Rein

PHOTO: Wikborg Rein senior lawyer Knut Hausken Magnussen (left), and Wikborg Rein partner Elise Johansen (right). Wikborg Rein

Banking, borrowing and deficits

When calculating and reporting for individual vessels, the FuelEU Maritime regulation allows companies to bank their vessels’ overcompliance surpluses for use in the next reporting period. They can also borrow an advance compliance surplus from the next reporting period, meaning they will have to burn more fuels with lower GHG intensities the next year to make up for what they borrowed. If an advance surplus is borrowed, an amount equal to the amount borrowed multiplied by 1.1 is subtracted from the vessel’s compliance balance for the next reporting period, effectively meaning that a penalty of 10% is applied.

But, if vessels are participating in a pooling arrangement there are certain restrictions in relation to banking and borrowing. If the total pool compliance results in a compliance surplus for an individual vessel participating in the pool, then this surplus may be banked for the following reporting period. However, for vessels participating in a pooling arrangement, it will not be possible to use the rules on borrowing advance compliance surpluses.

“The rules are a bit different depending on whether you calculate and report on an individual level or if you participate in a pooling arrangement. This must be taken into account when deciding whether to participate in a pool or not,” Magnussen says.

The responsible entity and the flexibility of the pooling arrangements

Explaining the legal provisions, Magnussen says the responsible entity under the FuelEU Maritime Regulation is the "company". This may be the shipowner. However, if another entity such as a manager or bareboat charterer has assumed the responsibility for the operation of the vessel from the shipowner and has agreed to take over all the duties and responsibilities imposed by the ISM Code, the manager or charterer will be responsible.

If a pooling-arrangement is entered into, the company must register its intention to include the vessel's compliance balance in the pool. There is no limit on the number of vessels that may be included in the pool, but the allocation of the total pool compliance balance to each individual vessel, and the verifier selected for verifying that allocation, must be registered. “Even if you have a pool of 100 vessels, you would have to say that for vessel A the compliance is 110%, for vessel B its 90%, and so on. So, it creates more flexibility, but you still need to specify the allocation of the total pool compliance balance on a vessel level,” Magnussen says.

Another important aspect of the pooling arrangement is that a pool may contain vessels which are controlled by two or more different companies, for example, two different managers. The only additional requirement for this is that the registered pool details are validated by all of the companies participating in the pool. According to Magnussen, this flexibility means that manager(s) which operate(s) vessels with low GHG intensity potentially could seek to obtain payments or other commercial benefits as a condition for including its vessel in a specific pool. Vessels with low GHG intensity will be in demand as they may be used in a pool to offset the potential non-compliance of other vessels through the allocation of the total pool compliance balance.

The FuelEU Maritime rules apply for voyages between EU ports (100% of the energy used), and for outgoing and incoming voyages to an EU port (50% of the energy used). Other voyages are not taken into account. Including a vessel with very low GHG intensity which purely operates outside the EU will therefore not have any effect on the pooling arrangement.

The class and weight restrictions of vessels participating in a pooling arrangement are the same as for the FuelEU Maritime regulation in general. It is possible to include different types of vessels in the same pool, as long as they are larger than 5,000 gross tonnes and otherwise fall within the scope of the FuelEU Maritime regulation. However, a vessel may not be in more than one pool at the same time.

Multiple EU laws to make shipping greener

The effectiveness of FuelEU Maritime cannot be viewed in isolation. It has to be considered together with other EU mechanisms aimed at curbing the maritime industry’s emissions, argues Elise Johansen, Wikborg Rein partner and specialist in sustainability-, climate- and environmental law.

The EU’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) is the other major upcoming regulation shipping companies have to keep on top of. Firms will constantly have to calculate what the right financial decision is, and the EU’s legal landscape is very dynamic, says Johansen, who thinks we will see rapid developments in fuel technologies in the years to come.

“The intention behind all of these new regulatory efforts from the EU is to incentivise this industry to go greener, to do these kinds of necessary investments into more green solutions,” she says.

Incentivise first movers

Shipping companies with zero-emission vessels will to a certain extent be able to offset the negative consequences of oil-fuelled vessels in their own fleets or in other fleets through the pooling rules. The general idea here is to encourage first movers. An expensive first-mover vessel may be able to recuperate some of that high capex through selling its overcompliance as a commodity.

“The new law will provide legal certainty for ship operators and fuel producers and help kick-start the large-scale production of sustainable maritime fuels, thus substantially delivering on our climate targets at European and global level,” Spain’s transport minister Raquel Sánchez Jiménez said when the regulation was adopted by the European Council in July.

Shipping classification society DNV expects a secondary market to develop for GHG intensity compliance surpluses. Say a vessel continues to run on oil-based fuels and becomes non-compliant from the time the registration kicks in from 2025. It can then either choose to buy biofuels, pay a fine or buy another vessel’s overcompliance. We don’t yet know how the overcompliance will be valued, but it is unlikely to fetch a higher price than the total cost of non-compliance – both from financial penalties and reputational damage.

This is because in the absence of ships fitted with engines capable of running on zero-emission fuels, unscalable biofuels and fossil LNG will remain the main routes to compliance, Transport & Environment has argued. The environmental NGO has pointed out that the availability of biofuels will be insufficient to meet upcoming demand.

And for those considering a business-as-usual approach, Magnussen confirms that the penalties for failing to meet compliance are non-negotiable.

“…ships that do not meet the limits on the yearly average GHG intensity of the energy used on board should be subject to a penalty that has dissuasive effect, is proportionate to the extent of the non-compliance and removes any economic advantage of non-compliance, thus preserving a level playing field in the sector,” FuelEU Maritime reads.

The consequences of non-compliance have been specified in the regulation, Magnussen says. It will first and foremost result in payment of penalties. However, more severe consequences may also be applicable in the event of a continued breach, such as an expulsion order and flag detention.

By Konica Bhatt and Erik Hoffmann

Please get in touch with comments or additional info to news@engine.online